Guide to adding citable supplemental material to any paper

Adding supplemental material to any paper is as easy as:

- making a GitHub repository packed with supplemental goodness

- using Zenodo to assign your repository a citable DOI

- citing your DOI-minted repository in your article

- minimal effort bonus: use GitHub pages to turn your supplemental material into a website

An academic publication’s supplemental material is that ill-defined thing you throw all of the extra content that could not be jammed into your original submission. E.g., extra analyses, dope videos, all of your raw data files, source code, et cetera. For computational researchers, including (or pointing to) the source code used to conduct our experiments is a critical step toward ensuring reproducibility.

During my time as a graduate student, I’ve learned that through the combined powers of public GitHub repositories and Zenodo, I can include as much supplemental material as I’d like with any publication, regardless of the publication’s venue. In fact, any academic publication that leans on software for experiments and/or data analyses has no excuse for not having quality supplemental material. The practices of copy-and-pasting source code into PDFs (yes, this is a real thing that I have encountered) must end!

Why spend actual time writing supplemental material?

Supplemental material is an opportunity to present all of those exploratory experiments, analyses, and visualizations that didn’t make it into the final manuscript. This gives you a chance to shout “hey, look at all this work that went into the making of this work”. Furthermore, supplemental material affords a platform for communicating the mountain of exploratory and negative results that your final results are built atop.

Most importantly, supplemental material should assist your methods section, helping others (or future you) to reproduce and extend your work. Often the space alloted to a paper’s methods section cannot accommodate a full ‘how to’ guide for reproducing your work. Supplemental material, however, can have all the space you need! You can include all of your (hopefully commented) source code and provide step-by-step guides to compiling and running your experiments.

Adding supplemental material to anything

I typically use two services to make my supplemental material happen:

You’ll need an account on both services. Accounts are free, though, so no worries there.

Setup a GitHub repository to house your supplemental material

I typically manage all of my projects start-to-finish on GitHub. Version control is a wonderful thing, especially for collaborative projects.

There’s a huge community that uses GitHub, so it’s not hard to google for solid tutorials. GitHub’s own guides are often a solid place to start for the basics. See also this starter guide on using git or this more advanced guide from a software development workshop run by the digital evolution lab during summer 2020.

Make your GitHub repository citable

I’ll outsource this step to GitHub’s very nice guide for making your repository citable with Zenodo: https://guides.github.com/activities/citable-code/. You’ll need a Zenodo account for this bit.

Cite your repository

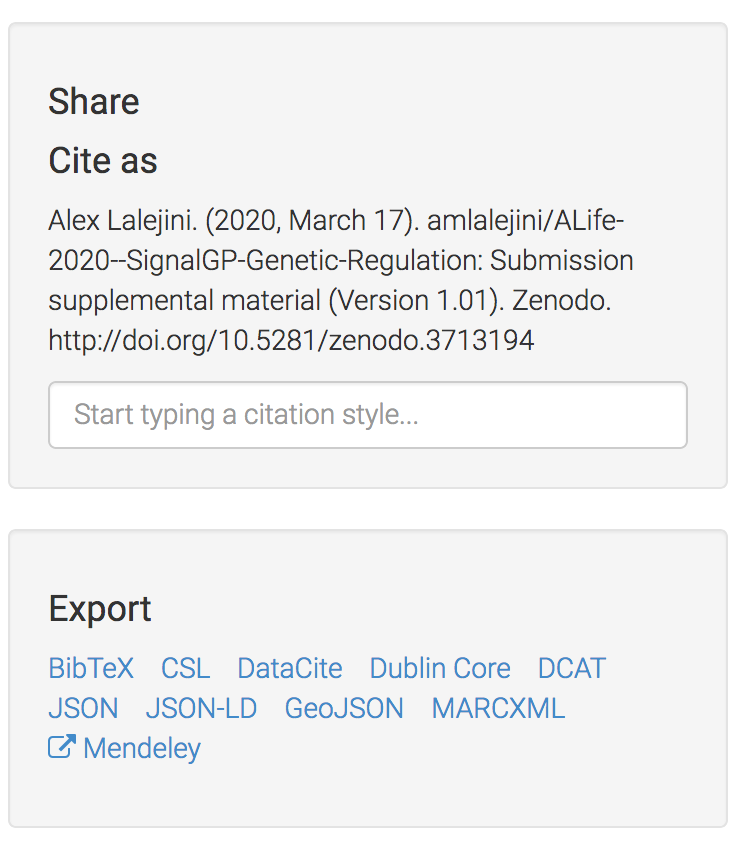

Zenodo makes this part easy. Just navigate to the Zenodo’s record page for your repository and look for the ‘Cite as’ box, or even more conveniently, the Export links to download the citation in your preferred format.

Add the reference to your paper’s reference list and cite away!

Make sure that the actual DOI for your repository appears in your reference; otherwise, it may be hard for anyone interested to actually find your repository.

Bonus: make your supplemental material web-accessible

I’m a big advocate for using GitHub pages to generate and host static websites with absolutely minimal effort (and at no cost). Making a website for a repository is actually as easy as toggling a switch in your repository’s settings. This is also a fantastic way to create and maintain personal web-sites (e.g., http://mmore500.com/, https://alackles.github.io/).

Again, I’ll outsource the how-to to one of GitHub’s own guides: https://guides.github.com/features/pages/.

Under the hood, GitHub uses Jekyll to turn your repository’s content into a static site. You can go as wild or as tame as you’d like on the website generated.

Once GitHub pages is flipped on, you can do things like…

- Convert your data into nice, annotated HTML pages that you can link folks to.

- I do the vast majority of my data and statistical analyses using R. Using R markdown, it’s easy to embed analyses in a markdown document that can be compiled into a nifty HTML page.

- E.g., source file, resulting html file

- Converting from other common data analysis setups (e.g., Jupyter notebooks) to web pages is also not difficult. Just google around for how to convert your analysis setup of choice!

- You can also write cool JavaScript (or C++ compiled into JavaScript via Emscripten) web applications and embed them into your web-accessible supplemental material.

- E.g., fitness landscape visualizations by Emily Dolson: https://emilydolson.github.io/fitness_landscape_visualizations/

Writing good supplemental material

Bad supplemental material doesn’t go far in improving your work’s reproducibility. Please please please do not code copy and paste code directly into a pdf.

If your source code is incomprehensible or you do not give gentle guidance on how to re-run an experiment, no one (including future you) is likely to spend the requisite time to resuscitate, replicate, and extend your project.

Just tossing code and analysis scripts into a citable GitHub repository does not make for good supplemental material. (though it is still better than pasting into a pdf)

Here are a few guidelines that I aspire to follow when I make supplemental material:

- Provide a brief, high-level overview of the project (motivations, experiments, findings).

- Pictures, pictures, pictures! Use all of those cartoons/diagrams you had to cut from your paper!

- Add a step-by-step guide to re-rerunning your experiments.

- List all of your external dependencies, and if possible, link to the exact commit of any other repositories someone needs to download to run your software.

- Bonus points for packaging everything up into a Docker or Singularity container.

- To check the quality of your guide, you can follow it yourself on a fresh virtual machine.

- Provide a brief organizational guide for your repository.

- Where is your experiment code? Where are your analysis scripts? et cetera

- You can write README files for relevant directories in a repository, which will render nicely on GitHub when someone clicks into the directory.

If you’ve done a cool thing with your supplemental material or have experiences to share, let me know!